“There were indications that the coronavirus was negatively impacting travel and tourism in the U. S. Manufacturing activity expanded in most parts of the country; however, some supply chain delays were reported as a result of the coronavirus and several Districts said that producers feared further disruptions in the coming weeks.” The Beige Book, Federal Reserve, March 4, 2020

Two weeks prior to their regularly scheduled mid-March meeting, the members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) voted unanimously to cut their target policy rate by 50 basis points to the 1 to 1¼ percent range. Policymakers attributed their exceptional decision to the “evolving risks” posed by the coronavirus.

This move was the first inter-meeting policy rate shift, and the largest cut, since late 2008, at the depth of the financial crisis. Moreover, this time the move came against the background of a strong economy: the unemployment rate is at a 50-year low of 3.5 percent, monthly job gains are averaging well over 200,000, and a simple nowcast points to first-quarter GDP growth of better than 3 percent. Not surprisingly, some skeptics view the Fed’s move as yielding to President Trump’s sustained pressure for lower rates (see our earlier posts here and here).

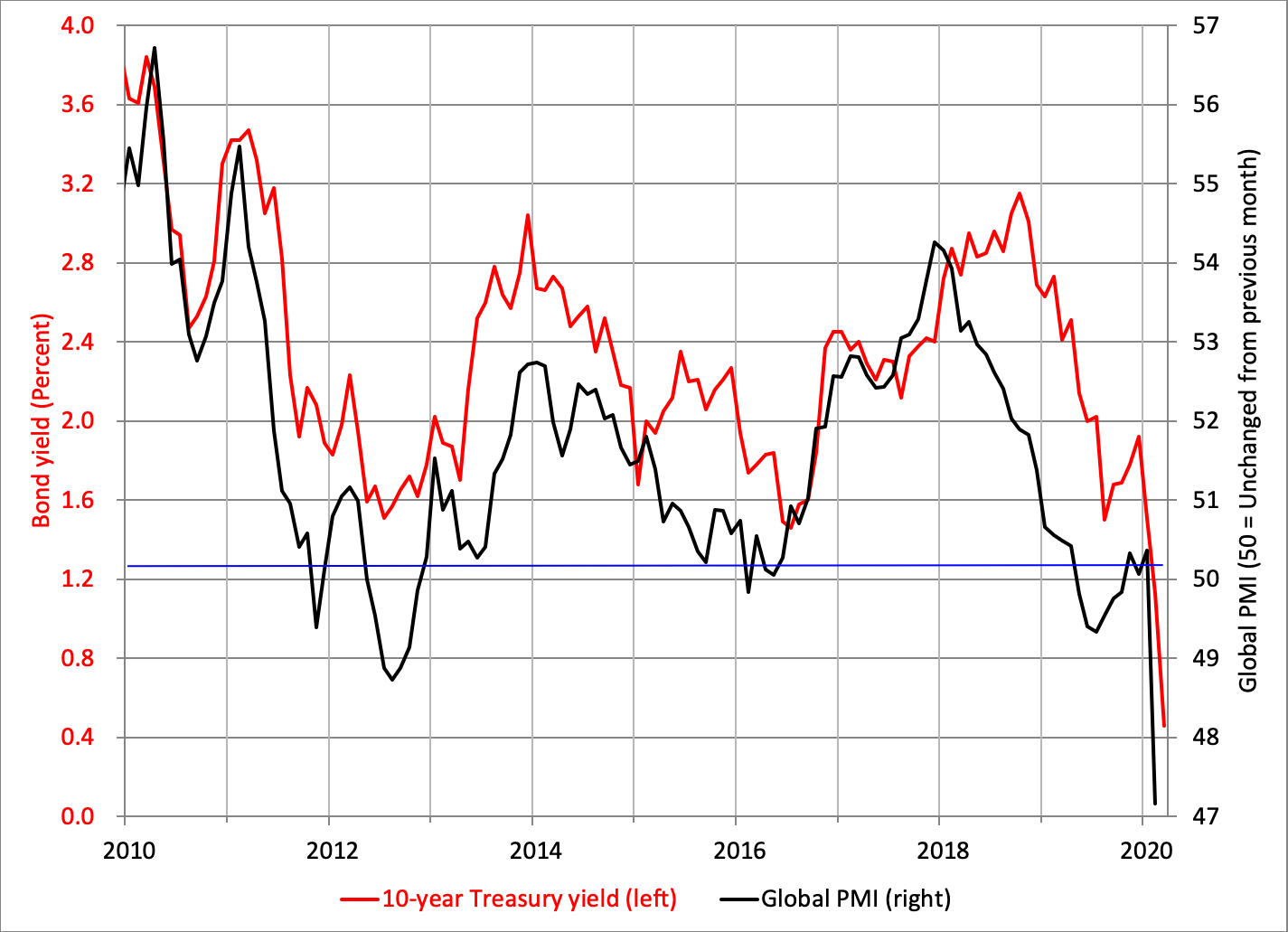

Nevertheless, based on futures prices, market participants anticipate a further 75-basis-point cut in the target federal funds rate this month! Reflecting the impact of the coronavirus, forecasters’ projections for 2020 growth are sharply lower, with some pointing to an outright recession. Following the February drop in global manufacturing, the 10-year Treasury yield has plunged to a record low of less than 0.5 percent, more than a full percentage point below its level just six weeks earlier (see chart). In addition, market-based long-term inflation expectations for the consumer price index are now below 1.5 percent. Adjusting this for the difference between the CPI and the Fed’s preferred price index of personal consumption expenditures, five-year ahead inflation expectations are now only about 1.3 percent, well below the Fed’s 2-percent target. If policymakers were really surrendering to political pressure, we would think that bond yields and inflation expectations would be rising, not falling.

Global purchasing managers index and the 10-year Treasury yield

Notes: A score above (below) 50 on the global PMI indicates that manufacturing is expanding or contracting from the previous month. Sources: FRED and courtesy of Deutsche Bank.

The coronavirus has thrust us into uncharted territory. Do central bankers really have any tools to guide us back to safer ground?

In the remainder of this post, we discuss the importance for policymakers of distinguishing between shocks to aggregate supply and demand. Importantly, while monetary policy can combat demand shocks, it can do nothing to cushion the impact of reductions in supply without sacrificing the commitment to price stability. Yet, the coronavirus shock involves some as-yet-unknown mix of these two very different types of shocks. Moreover, given the limited amount of conventional policy space, and that the central bank’s tools generally are more effective at fighting inflation than deflation, with inflation expectations sinking there is a good case for the FOMC to act rapidly and aggressively. Under these circumstances, it is better to go too far too fast and fix the consequences than it is to wait and see what the coronavirus wreaks.

So, taking a step back, what are typical shocks to aggregate supply and aggregate demand? Technological progress allows the economy to expand without an increase in key inputs (such as capital, labor, or natural resources). It boosts supply and lowers inflation. Conversely, obstacles to trade—such as tariffs or an oil embargo—that boost input costs tend to lower output, while raising inflation and inflation expectations. The oil shocks of the 1970s and of 1990 are typical examples of supply shocks that drove output down and inflation up. On the demand side, increases in (household or business) confidence, wealth, government spending, and net exports, as well as tax cuts, will result in higher levels of activity and higher inflation.

Distinguishing shifts in supply from those in demand is essential for monetary policymakers. The reason is that demand shocks move output and inflation in the same direction—a positive shock boosts both, while a negative shock depresses them—so policy that resists a demand shock stabilizes both activity and inflation. In contrast, supply shocks move output and inflation in opposite directions: a positive shock raises output and lowers inflation, while a negative shock does the reverse.

Monetary policy influences demand, moving output and inflation in the same direction. Consequently, central bankers can help secure price stability by resisting shocks to aggregate demand: lowering the policy rate when demand falls short of the level of activity consistent with stable inflation, and raising it when demand exceeds it. Put simply, monetary policy is about managing aggregate demand.

Supply shocks are different, because central bankers have no tools that move output and inflation in opposite directions. In the face of a negative supply shock, a credible commitment to low inflation means accepting that output will fall. Attempts to resist the oil shocks of the 1970s helped fuel inflation. Today, inflation-targeting central banks generally do not resist supply shocks, even if they trigger a recession. They do not manage aggregate supply.

Importantly, both demand and supply shocks can and do trigger recessions. The following chart shows how inflation and equity prices changed in the 10 U.S. recessions over the past 70 years. Note that equity prices almost always decline significantly—reflecting the prospective fall in profits—but inflation does not. We can use the evolution of inflation to help distinguish supply- and demand-driven recessions.

Changes in CPI inflation (percentage points) and the S&P Composite (percent) in U.S. recessions since 1950

Note: The change of inflation is the difference between annual CPI inflation in the month prior to the start of the NBER business cycle peak and in its level at the trough. The percent change of the S&P Composite compares the level six months prior to the business cycle peak with the index trough during that recession. Sources: FRED and Shiller.

Looking at the chart, we see that the only unambiguously supply-driven recession since 1950 was in the early 1970s when oil prices quadrupled over a period of six months. In contrast, negative demand shocks appear to dominate U.S. business cycle history, with sizable inflation declines in four downturns. At the same time, in four other recessions, inflation barely moved. Aside from the brief 1980 downturn, when there was little time for inflation to respond, this pattern suggests the offsetting presence of both demand and supply shocks. The 1990-91 recession, where leading indicators had already begun slipping when the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait set off a spike in oil prices, is a good example. So, a rough accounting is that of the 10 past recessions, one was clearly supply driven, four were demand driven, four were some mixture of the two, and one was too short to tell.

This brings us back to the coronavirus, with its likely effects on both supply and demand. The FOMC’s latest Beige Book highlights supply chain concerns (see the opening citation). Going forward, social distancing—both compulsory and voluntary—is likely to hinder labor supply. The longer the disruption, the more likely that firms also will have difficulty obtaining key intermediate inputs, hindering production. And, while activity in China—the center of the global manufacturing supply chain—may start recovering soon, the pathogen already has spread to more than 100 countries, as well as to 34 U.S. states. As a result, investors now recognize that these supply disruptions could broaden and extend well beyond a few weeks or months.

Indeed, for people to regain the confidence needed to go about their normal daily lives—including going to their place of work—governments will need to demonstrate some combination of: (a) credible testing to demonstrate the population is nearly virus free; (b) effective quarantine or social distancing of those infected; and (c) successful treatment that limits the impact of the disease. The lack of U.S. government preparation—evidenced by the continued shortfall of test kits—serves to delay the hoped-for return of confidence.

Of course, no central bank has tools capable of assuaging people’s fears of contracting the coronavirus. Monetary policy is unable to address these, or any other, supply constraints. Yet, policymakers cannot ignore the prospective weakening of demand. As people shy away (or are kept away) from places where the disease can be transmitted, businesses will lose revenues and some workers will lose their jobs. Amid high levels of business debt, this could easily trigger defaults as well (see the Federal Reserve’s May 2019 Financial Stability Report). At the same time, the fact that nearly half of households lack emergency savings likely will amplify the impact of wage losses on consumption (see our post). Even when private spending recovers, the “temporary” losses are not going to be replaced.

Given these countervailing forces, would a wise FOMC simply wait to see if inflation rises (from a dominant supply shock) or falls (from a dominant demand shock)? If inflation were at or above the Committee’s 2-percent target, and the steady-state nominal interest rate were about 5 percent (leaving plenty of room to cut as needed in a recession), the case for postponing action would be strong. The benefit of waiting would be to avoid stoking inflation, while the costs would be limited, since policymakers would still have time to lower rates sharply and counter weak demand.

However, current conditions are very different from the norms of the past 70 years. Today, somewhat higher inflation and a rise in inflation expectations would be welcome. Combine that with the limited scope for conventional monetary policy easing, and the natural conclusion is that central bankers should err on the side of aggressive action. If, as some observers suggest, fiscal policymakers also will need to act to counter the economic consequences of the coronavirus (see, for example, Cochrane and Furman), then early Fed action puts Congress on notice that the stabilization ball is now squarely in its court.