“…the new tools have been quite effective, providing substantial additional scope for monetary policy despite the lower bound for short-term interest rates.”

Ben Bernanke, “The New Tools of Monetary Policy,” AEA Presidential Address, January 4, 2020.

In many advanced countries, lowering the policy rate to zero will be insufficient to counter the next recession. In the United States, for example, with the target range for the federal funds rate at 1½ to 1¾ percent, there is little scope for the nearly 5 percentage-point easing that is typical in recent recessions (see, for example, Kiley).

This is the setting for this year’s report for the U.S. Monetary Policy Forum, written with Michael Feroli, Anil Kashyap and Catherine Mann. Our analysis focuses on the extent to which the “new tools” of monetary policy—including quantitative easing, forward guidance and negative interest rates—have been associated with an improvement of financial conditions. The idea is that the transmission of monetary policy to economic activity and prices works primarily through its effect on a broad array of financial conditions.

The USMPF report does not challenge the views of many researchers and of most central banks—summarized by the opening quote from Ben Bernanke—that the new monetary policy (NMP) tools have an expansionary impact even at the effective lower bound for nominal interest rates (see also the 2019 report from the Committee on the Global Financial System). However, we find that these new tools generally were not sufficient to overcome the powerful headwinds that prevailed in many advanced economies over the past decade.

Our conclusion is that central bankers should clearly incorporate the new tools in their reaction functions and communications strategies, but should be humble about their likely success in countering the next recession, at least in the absence of other supportive actions (such as fiscal stimulus).

In the remainder of this post, we summarize the USMPF report’s analysis and conclusions.

The key challenge in assessing the effectiveness of NMPs is to identify causal effects. To do so, most observers rely on event studies that measure the impact of NMP policy announcements on long-term bond yields over a very short time interval of hours or days (see, for example, Krishnamurthy and Vissing-Jorgensen). In the face of some skepticism (see, for example, Greenlaw et al), Bernanke’s 2020 AEA Presidential Address defends these event studies and marshals a range of other evidence (including tests using structural models of the economy) in support of the NMP tools.

Recognizing that causality is more difficult to determine over longer, economically meaningfully periods of quarters or years, we take an agnostic view of NMP effectiveness. Rather, we ask whether the NMP tools were sufficient (on average across countries over the past decade) to counter what were usually quite adverse financial conditions. In addition, rather than limiting the focus to the relationship between NMP policies and bond yields, we explore policy’s impact on broader financial conditions—ranging from equity returns and equity volatility to credit spreads and nominal exchange rates—that play a role in transmitting monetary policy to economic activity. Importantly, we find that there is a notable global factor driving financial conditions over which central banks appear to have limited influence. This narrows the scope for policy impact.

After controlling for the global factor, we examine the impact of NMP tools on two indexes of domestic financial conditions in eight countries. With the exception of the monetary base (which is a continuous proxy for balance sheet expansion), we measure NMPs using discrete-valued indicators that switch on (off) when policies are introduced (ended).

The following table highlights our very mixed results. A yellow-shaded (orange-shaded) cell indicates a statistically significant effect. The hope is that NMPs ease financial conditions, consistent with a decline of our domestic financial conditions indexes. When this is the case, we put a black minus sign (“–“) in the cell. In cases where we find a significant effect of the wrong sign, we put a red plus sign (“+”) in the cell. Gray cells are cases where the estimated coefficient is not different from zero at the 10 percent level; and a white cell signifies that the country did not use that tool.

Impact of New Monetary Policy Tools on Domestic Financial Conditions

Notes: Table reports the impact of various NMPs on domestic financial conditions. Yellow shading denotes a statistically significant impact (a t-ratio equal to or greater than 2.0) and orange shading indicates a t-ratio between 1.5 and 2.0. Gray means no statistically significant effect, and white means that the country did not use the tool, or that it is collinear with another tool. For the euro area countries, we use ECB assets in place of the monetary base. Source: Table 1 in USMPF (2020).

Of the 84 possibilities (cells that are not white), in only 24 cases did NMPs have a statistically significant impact with the expected sign (black “–“s). In 17 country-tool episodes, the sign was wrong and significant (red “+”s). In the United States, there are as many instances (three) when the NMP effect appears perverse as when it appears successful.

To be clear, the results in table do not allow us to assess causality. They are silent on the effectiveness of the tools in easing financial conditions relative to what they would have been in the absence of strong and intensifying financial strains. Put differently, we do not know the counterfactual: namely, how would financial conditions have evolved in the absence of any policy action? Instead, we find that the NMP tools typically were insufficient to overcome prevailing headwinds and deliver a net easing in financial conditions. In short, the new monetary policy tools were not enough.

Why is it so difficult to assess NMP causality directly? The simple answer is that, aside from negative interest rates, policymakers typically invoked these tools when financial conditions were tight (and possibly getting tighter). This pattern of endogenous policy response to deteriorating financial conditions complicates any statistical assessment.

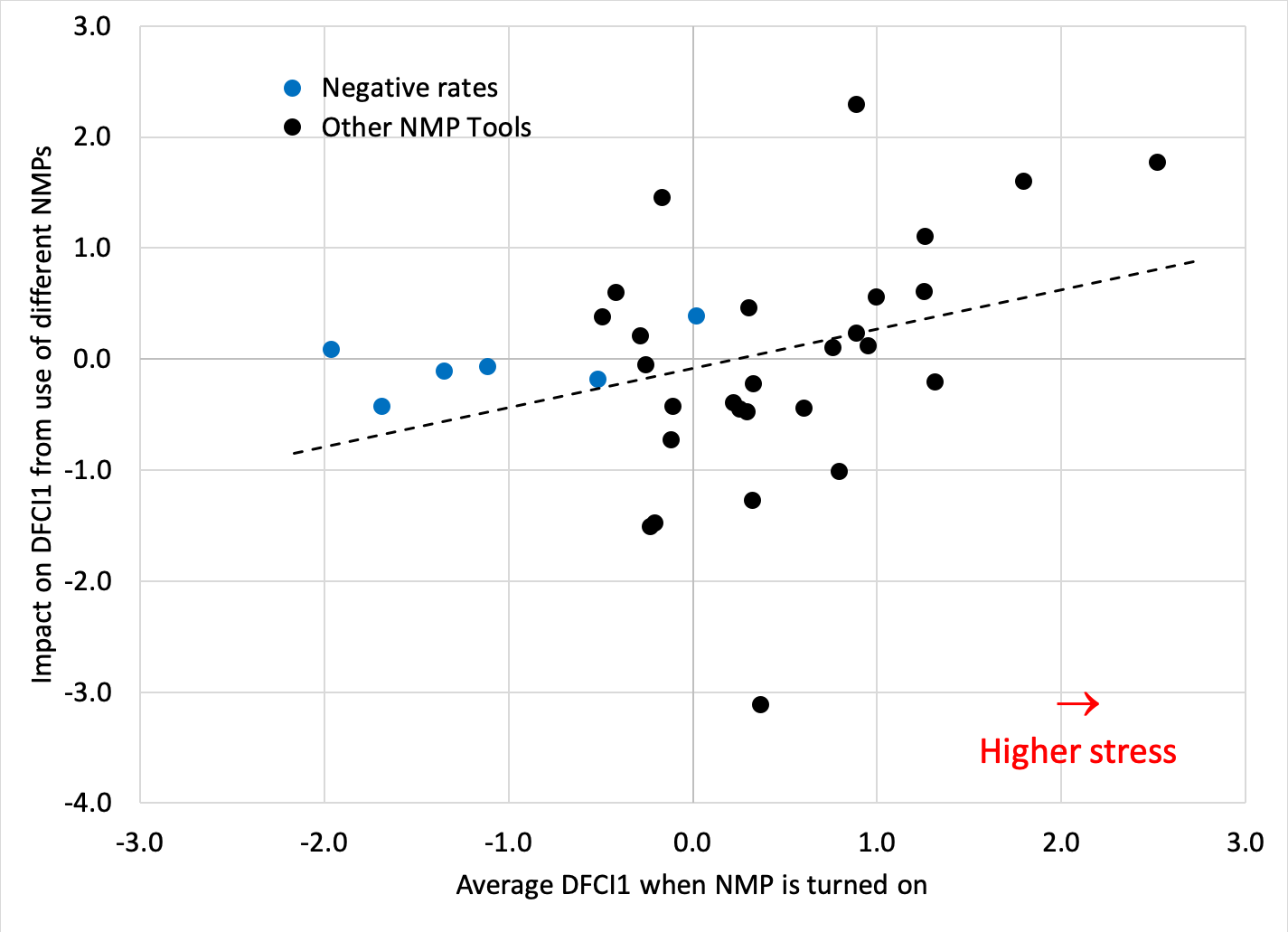

Consider, for example, the following chart. The horizontal axis measures the tightness of financial conditions when the NMP tool is activated, while the vertical axis shows our estimate of the impact of the tool on financial conditions (the unconditional, long-run elasticity of the first of our two domestic indexes). The positive slope of the fitted (dashed) line indicates that the net impact is smaller (or even perversely positive) when initial financial conditions are tight. But that may simply reflect the persistence and force of the prevailing headwinds, rather than the independent (exogenous) impact of the NMP tool.

Level of Initial Domestic Financial Conditions and Policy Efficacy

Note: Each dot represents a country-NMP tool pair. Source: Figure 7 in USMPF (2020).

The inability to use these data to establish causality imposes considerable limitations on inference. Nevertheless, there are important things we can learn from the analysis. For example, it turns out that state-contingent forward guidance is the NMP tool most frequently associated with a significant improvement of financial conditions. And, as the chart above shows, negative interest rates—alone among these NMP tools—were introduced when financial conditions already were loose (these are the blue dots on the left). That negative interest rates appear to have relatively limited effect under these conditions (the blue dots are close to zero on the vertical scale) is consistent with research pointing to asymmetric impacts of monetary policy.

So, what can we conclude? Careful empirical research generally finds that NMP tools provide some support to economic activity. This is likely to be an important premise of the Federal Reserve’s ongoing monetary policy review (see, for example, the discussion of the USMPF paper by Fed Governor Lael Brainard). However, the results of our study leave little room for complacency. Most important, long-term yields are likely to be far lower going into the next downturn than in any recession over the past 75 years. This will limit the potential for any monetary policy tools to ease financial conditions.

The bottom line: Policymakers should communicate a clear plan for how they will use NMP tools in the next downturn so that financial market participants can anticipate central bank behavior and speed its impact on financial conditions and the economy. In addition, as the next recession approaches, policymakers should be prepared to employ NMP tools early and aggressively when it is still feasible to stabilize prices and economic activity. The concerns that NMP tools would foster inflation risks—so prevalent a decade ago—have proved unfounded. Consequently, the limited success of NMP tools in easing financial conditions justifies more activist policy, not less. It also means that monetary policy should not be the only game in town.

Acknowledgements: We thank our co-authors for the opportunity to collaborate on the 2020 USMPF paper. We also are very grateful to our discussants, Federal Reserve Board Governor Lael Brainard and Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta President Raphael Bostic.